The art of slowing down

It seems the recipe for a relaxing weekend is art, wine, and not working on side projects

“lol Milwaukee?”

I received that text more than once after landing.

The sun was out, the tiki bar was open, and the sidewalks were crowded with bistro tables and popup biergartens. This felt more like Miami, minus the salty air. Apparently August is when Lake Michigan turns into a tropical getaway — complete with beach volleyball and frat pledges ordering each other to cart around bins of Spotted Cow. This was Milwaukee summer: where 10 months of pent-up disdain for the snow comes out for birthday beer miles and Hugh Jass Pretzels.

I had promised a friend since he moved out of San Francisco that I’d come visit. That was… nearly five years ago? Hard to say. There is no seasonal passage of time in SF. But since then, this friend and I have left our big boy jobs, taken the executive leadership roles of a startup, and are planning his officiating of my wedding. It felt right to finally take the trip. Plus, he has a very good wine collection and the snow had finally melted.

As it turns out, I needed this weekend more deeply than I was willing to admit to myself. It took flying 2,000 miles, a forcible pause of all of my side projects, and ranting about modern art for me to recharge. And suddenly, Milwaukee became the highlight of the summer.

Some light reading on the plane

Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility has quickly become one of the most important essays I’ve ever read. Even in my role, it is constant battle to explain why design, writing, art, content creation, and creativity is a valuable resource in an industry that is optimized for revenue growth. A teammate from our Content team recently shared (paraphrased) “it’s difficult to exist in a role in which we must constantly both prove our own abilities through the quality of our work and justify our existence in the company.” And then we read this work by Benjamin: a piece that explains the role of art in our everyday lives and how experiencing uniqueness can influence action. While reading, I was overwhelmed with the feeling of being seen and the wanting of being equally seen by my peers. I’m going to insist that each of them now read it.

Benjamin goes pretty deep into his explanation of art’s “aura,” or the unique experience of each artwork in the time and place in which it was created. How being there is the experience, and how photos and retellings from others will never invoke the same feelings.

Queue me immediately weaponizing that interpretation by dragging my friend to the Milwaukee Art Museum and ranting about abstract expressionism.

Feeling something in an art museum

A night of drinking finer wine than will ever grace my collection revealed two facts that horrified me:

My host, a local of nearly five years and a self-proclaimed man of class, had never visited the Milwaukee Art Museum

I was among a group who believed expressionism and abstract art to be contrived and meaningless

Crack another bottle, let’s hop into it.

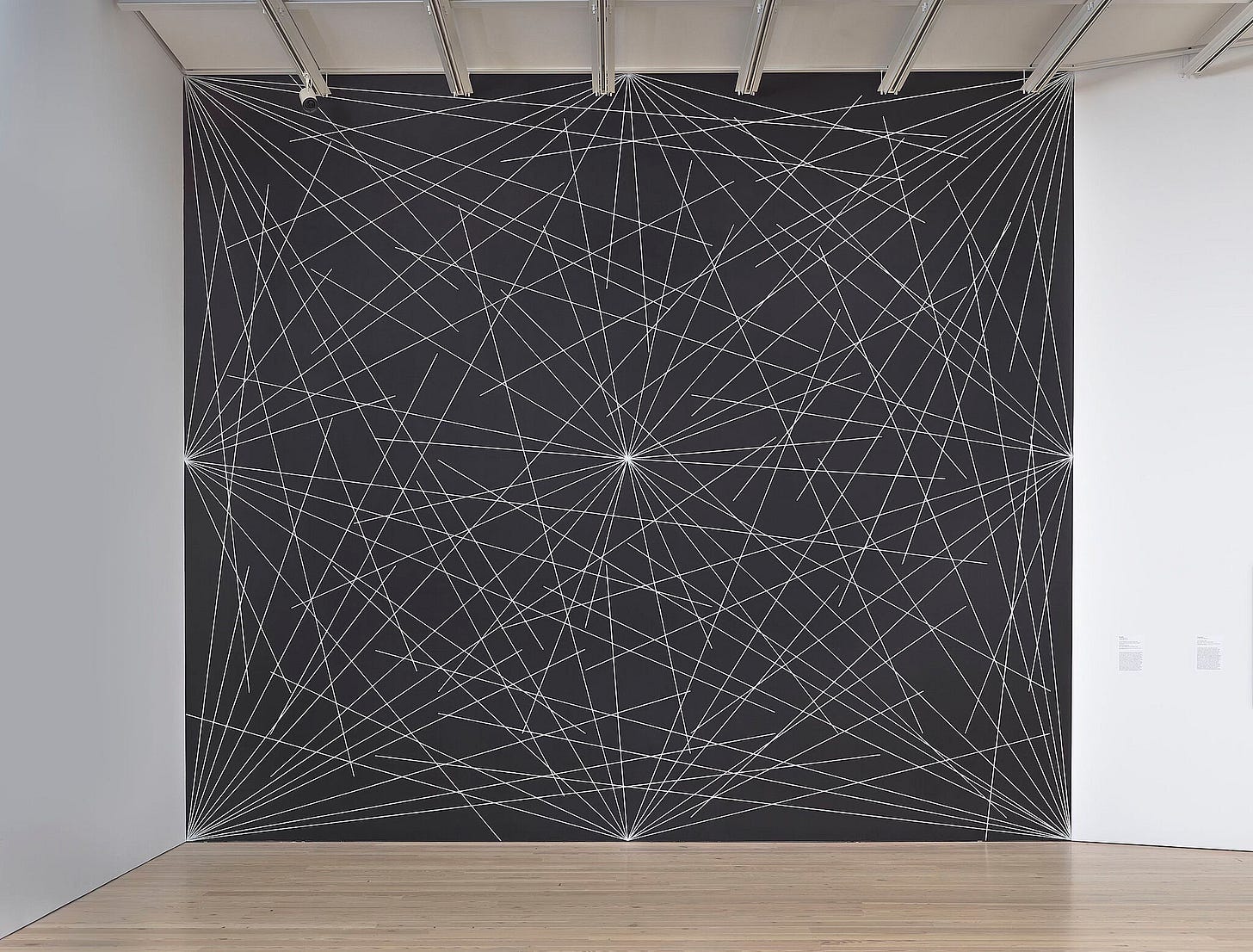

Sol LeWitt is one of the greatest conceptual and minimalist artists to have ever lived. He pushes our understanding of what it means to create art, daring to ask if the concept of the piece is more important than its form. He infamously created sets of instructions on how to create immersive pieces directly into galleries, often drawn directly onto the walls with simple pencils or pastels. They’re unique. They can never be replicated. And there is so much room for interpretation that even if another piece is made using the same instructions, the human element always introduces variance. It begs an unanswerable question: is LeWitt’s art the instructions that he scribbled onto a scrap of paper or the 12’ wall of abstract lines that were drawn long after his death? And it means that the LeWitt you're looking at in Milwaukee will invoke a flurry of emotion that feels completely different than the LeWitt in the Whitney.

If that isn’t Benjamin’s definition of aura, I don’t know what is.

Contemporary painting, modern art, minimalism, and abstract expressionism are more important than any of their periodic predecessors. They push our boundaries of understanding — they beg how to share one’s subconscious on a canvas, they value expression over commemoration, they make you want to feel instead of see. And while I value what the old classics did to lay a foundation for modern art, I will always contend that the only important thing to come from the Renaissance was Prussian Blue.

Unfortunately for my host, the Milwaukee Art Museum has a surprisingly robust collection of the greats (along with some local + young additions) and he got to experience my rants for most of them:

David Schnell

Katharina Grosse

Gerhard Richter

Sol LeWitt

Agnes Marten

Ad Reinhardt

Susan Rothenberg

Tony Stubbing

Angelo Ippolito

Cy Twombly

There I was, the old Mac — running around an art museum with a sketchbook and a Blackwing pencil being absolutely insufferable. By the end, I had hit the full bingo card’s worth of “well actually,” “DiD yOu KnOw,” and “what’s fascinating about this piece is how the artist used a foreground element to somehow force one-point, two-point, and three-point perspective all into the same piece.” It was horrible. It was beautiful. My own little renaissance.

Fine wine, fine art, and sleeping more consecutive hours than usual

A typical weekend in the studio looks like piles of magazines and inked rags. It smells like freshly sharpened graphite pencils and stale coffee. It feels like throwing myself at side projects until I crawl into bed at 2am with the satisfaction that can only come from exhaustive creative output.

I often forget to relax.

I’m even writing this update with a nasty cough — the symptom that Meghan has come to reference as my ‘full body shutdown’ that seemingly always comes after a particularly stressful work week.

Alas, rest is good. I hate to admit that lounging around the parlor with a glass of wine and a midnight espresso while discussing modern art and philosophy felt both ridiculously cliché and like the thing my body needed most. It’s okay to not be productive. It’s okay to open the windows, stay barefoot for the day, and read a book. It’s okay to leisure.